In the good old days of the City, it used to be said that the raising of the governor of the Bank of England's eyebrow was a more powerful instrument in the Square Mile than any law a regulator could muster.

Titans of finance would be summoned to what are still known as "parlours" in Threadneedle Street for a cup of tea and a fireside chat with the governor of the day – whereupon the eyebrow, either metaphorically or literally, would be raised.

The shock departure of Xavier Rolet, chief executive of the London Stock Exchange, to be followed in due course by his chairman, Donald Brydon, shows the governor's eyebrow remains a formidable weapon.

:: LSE boss quits a day after Carney comments

For the news comes just 24 hours after Mark Carney, while publishing the results of the Bank's latest stress tests, declared himself "mystified" at the spat between the two men – which flared up when the LSE said Mr Rolet would step down by the end of 2018 and an activist shareholder, Sir Chris Hohn, demanded instead that Mr Brydon step down and Mr Rolet remain in place until 2021.

Asked about the dispute, Mr Carney said: "Xavier Rolet has made an extraordinary contribution as head of the LSE over the last nine years. But everything comes to an end.

"We were appraised of the succession plan before it was announced – the agreed succession plan. I can't envision a circumstance where the CEO stays on beyond the agreed period."

This was taken as a signal to Mr Rolet, who has garnered many plaudits for his successful stewardship of the LSE, to clear his desk.

For many in the City, the restoration to power of the governor's eyebrows has been reassuring.

Pre-1997, they were how the Bank ordered commercial lenders to row back on their lending, to curb riskier activities, or bolster their capital position.

Sir Win Bischoff, the former chairman of Lloyds Banking Group and before that a veteran investment banker at Schroders and Citigroup, described the process thus: "He would say, 'Win… is this the right way of going about it?' or 'Should you be in this kind of business?'

"You knew they were taking it seriously and using their judgment that, perhaps, for your organisation, this was not the right thing to do."

Over the years, arguably, those powers waned.

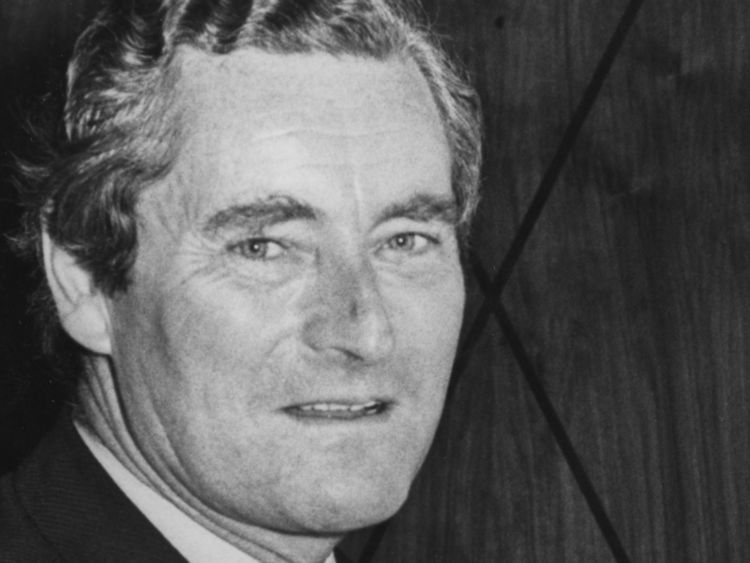

Robin Leigh-Pemberton, governor from 1983-1993, even joked at the time of his appointment that many in the City had "wondered whether my eyebrows were up to the job".

The subsequent collapse, on his watch, of Johnson Matthey Bankers in 1984 and BCCI in 1991 suggested that perhaps the system was not working.

The rise in power and influence in the City of foreign banks after 'Big Bang', in 1986, undoubtedly contributed to that sense.

But the power of the governor's eyebrow was eliminated altogether when, in 1997, Gordon Brown stripped the Bank of its regulatory oversight of the banking system and handed it to the newly formed Financial Services Authority.

The Bank retained oversight of financial stability but taking away its ability to actually supervise the activities of the banks and order them what to do undoubtedly contributed to the financial crisis.

When the coalition came to power, it restored those powers to the Bank, which in 2012 revived the tradition of the governor's eyebrows when Mervyn King ordered Barclays to replace Bob Diamond as chief executive.

Although the LSE is in theory regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority, which took on half of the old FSA's responsibilities (the other half, supervision of banks, insurers and investment firms, went to the Bank), Mr Carney has shown that the system is still functioning.

Mr Carney made perfectly clear that the LSE's activities are "systemic"; in other words, integral to the smooth running of the financial markets – and therefore falling under his purview.

For the LSE, meanwhile, this is an awful situation.

Mr Rolet, as shown by Sir Chris's campaign, has been an exceptional chief executive – taking its market valuation from £800m to more than £13bn today.

Yet it is not the first time in recent times that the LSE has suffered a sudden loss of its CEO.

In 1993, Peter Rawlins was ejected after millions were wasted on an electronic trading system called Taurus.

His successor, Michael Lawrence, went three years later after his attempts at modernisation were opposed by his board.

And in 2000, Gavin Casey was toppled when the LSE's members voted down his plans for a merger with Deutsche Boerse, a deal that ironically Mr Rolet subsequently tried and failed to pull off.

The tenure of his successor, Clara Furse, is largely regarded as a failure these days because of her failure to acquire the London International Financial Futures Exchange (LIFFE), which was instead bought by Dutch-based Euronext.

Mr Rolet was more successful than any of his four immediate predecessors.

The LSE will be lucky to get someone as good as him again.

More analysis & comment

- Previous article Why UK is being 'cagey' about Brexit divorce bill

- Next article Sky Views: Missing sub brings old foes together